Manacles, believed to be the ones used on Leo Frank during his abduction. [Van Pearlberg; photo Elisson]

There’s a nondescript spot on Georgia Route 120 - Roswell Road, as it is known heareabouts - just over seven miles from my home in East Cobb County, just a few feet past the Interstate 75 underpass. It’s where the old Frey’s Gin Road used to be, and today it’s a stone’s throw from Marietta’s iconic landmark, the Big Chicken. I was just a few hundred feet away from that spot yesterday as I stopped in at Harry’s Farmer’s Market to pick up a few foodly odds and ends.

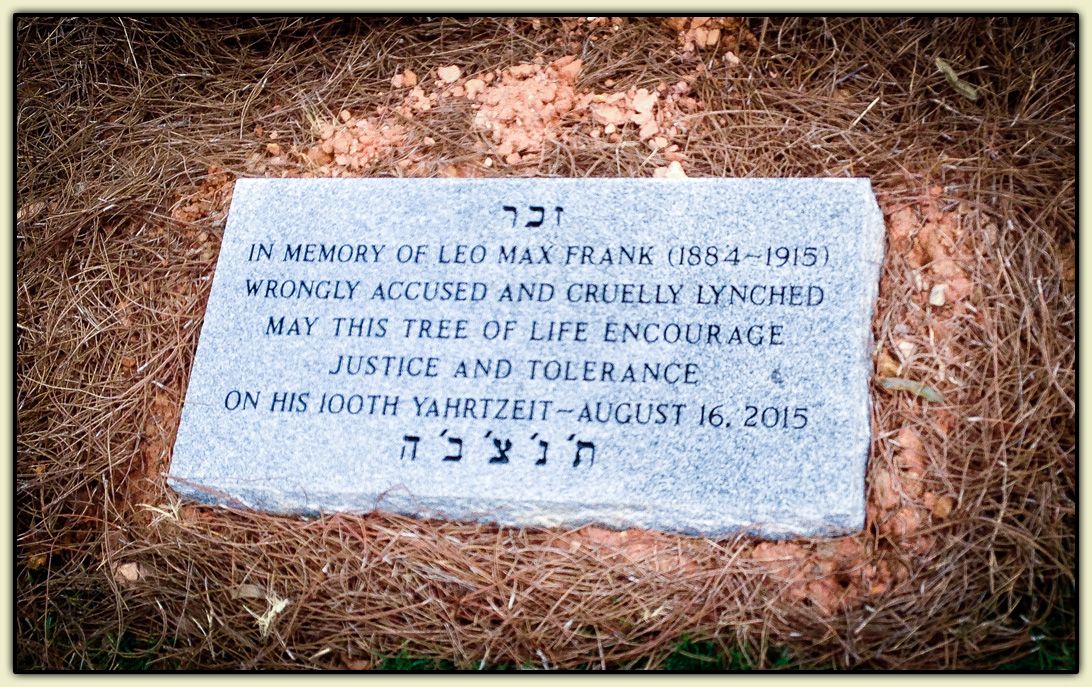

It’s a nondescript spot, but one with a tragic historical significance. One hundred years ago today, that is where Leo Frank was lynched.

Leo Frank’s story is a long and complicated one, one that still resonates powerfully today. But for years, it was spoken of in hushed tones if at all - by the perpetrators of the lynching and their descendants; and by the members of the local community, both Jewish and gentile. Discussion would not bring back the dead; discussion could only arouse old grievances, hates, and bitter feelings. But when an event is shrouded in silence, we learn nothing from it - including how to prevent similar tragedies in the future.

For those who are completely unfamiliar with the case, the bare-bones outline is as follows: On April 26, 1913, Mary Phagan of Marietta, Georgia - a thirteen-year-old employee of the National Pencil Factory in Atlanta - went to the factory to pick up her wages from Leo Frank, the factory superintendent. The following morning, her dead body was discovered in the basement. The investigation, rife with inconsistencies, eventually settled on Frank as the prime suspect, and an arrest followed. Frank was found guilty after a sensational trial. Appeals were denied; he was sentenced to hang. But two days before his term ended, then-Governor Slayton, who had become concerned that Frank’s trial could not possibly have been fair given the relentless media attention and the highly charged public opinion that prevailed, commuted Frank’s sentence to life in prison.

There was a group of state and Cobb county notables that were not having any part of what they perceived as a gross miscarriage of justice. They quietly laid plans to have Frank kidnapped from the state prison farm in Milledgeville where he had been lodged (and where an attempt on his life by a fellow prisoner had barely missed succeeding) - and on the night of August 16, 1915, an army of Mariettan stealth-ninjas extricated Frank from prison without a single shot being fired. After a seven-hour drive up country roads in the dead of night, the kidnappers arrived in Marietta. After alerting the locals - a lynching, after all, is no lynching without a crowd of excited locals to observe and cheer - Frank was hanged from an oak tree, his body left dangling for hours.

None of the kidnappers or members of the lynch party, and none of the conspirators who had made their dark arrangements, were ever charged with any crime... mainly because the people who would normally have been expected to enforce the law were all in on it.

There were profound implications. Jews who had been a part of the local community for decades understandably felt unwelcome; many deserted the South permanently. Members of a revitalized Ku Klux Klan burned a cross atop nearby Stone Mountain; on the other side of the cultural divide, the relatively new Anti-Defamation League found a sense of purpose. And the case receded into the shadows.

But in the mid-1980’s one Alonzo Mann, who had worked at the pencil factory as Leo Frank’s office boy, came forward to state that, on that fateful day in April 1913, he had seen Jim Conley, the janitor, carrying a girl’s body down to the basement. Conley had threatened to kill Mann if he spoke a word about what he had seen... and Mann, whose parents had sternly instructed him to keep his mouth shut, was never able to offer any exonerating testimony at Frank’s trial. Now Conley was dead, and an elderly, ailing Mann finally felt that it was time to speak out.

The authorities, of course, had been aware of Conley, and had briefly considered him a suspect. But Frank was a much better catch. Conley was just another black man, while Frank represented everything the average Southerner, only fifty years after the Late Unpleasantness, had come to resent. He was a wealthy, Ivy League-educated Northerner - and a Jew to boot. If he could be convicted, why, it would fit hand-in-glove with the narrative of continued Northern rapine and pillaging of the South. And one of those Christ-killers, too! We have us a real monster, boys!

Little Mary Phagan deserved justice. Instead, she got a circus.

Frank has since been pardoned by the State. His pardon did not address the matter of guilt or innocence in the Phagan murder, but was a recognition of the fact that the State had failed to try him fairly or to protect his person. Author Steve Oney, who researched the case for a full seventeen years before writing his book And The Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank, has said that he is 98% sure that Frank was innocent... but given the age of the case, there is always that nagging two-percent doubt. But - at least in my mind - Frank’s accusers failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he was guilty. Spectacularly failed.

But that mattered not. So strong was their belief in his guilt - pumped up by firebrand populist demagogues such as Tom Watson, publisher of The Jeffersonian - that facts were mere inconveniences to be swept away or ignored. The mobs chanted “Hang the Jew - or we’ll hang you!” during the trial, and an ad-hoc committee of the finest Mariettans eventually gave them what they wanted.

It is an object lesson on what happens when we allow ourselves to be carried on the tide of public opinion without taking the time to critically examine facts. When the narrative becomes a substitute for reality, we are in Deep Trouble... a tale especially cautionary in our days of social media, where everyone with a Twitter or Facebook account is a potential Tom Watson shouting into an echo chamber of like-minded souls.

It’s a full century later, and Cobb County now is home to a thriving Jewish community. It is where I have lived for over a third of my life. Meanwhile, I hope the ghosts of Mary Phagan - the first innocent victim of this tragedy - and Leo Frank, who was a victim no less than little Mary, are in Heaven sitting together, bemoaning the cruelty and stupidity of the humans that put them there before it was their time... and yet hoping for a better future for all of us.

Update: Steve Oney, in an article in The New Republic, writes about how the Frank lynching foreshadowed today’s polarized political climate.

No comments:

Post a Comment